A report by Hans-Herbert Dörfner, an expert with the Senior Experts Service (SES) in the Foundation of German Industry for International Cooperation, Bonn, who was seconded by the SES to a vocational college in Cibadak/Sukabumi on the Island of Java (Indonesia) to train indigenous specialist teachers there in the manufacture of European breads and baked products.

Do Confetti Stone, Black Forest Cherry or Romance Rosé please you? One might almost think they are names on a dessert menu, but in this case it’s about something different, namely shoes. High heels with a sweet “outer cladding”, to be precise. Responsible for the sweet footwear – which incidentally are actually wearable, although not edible – is Gunter Müller.

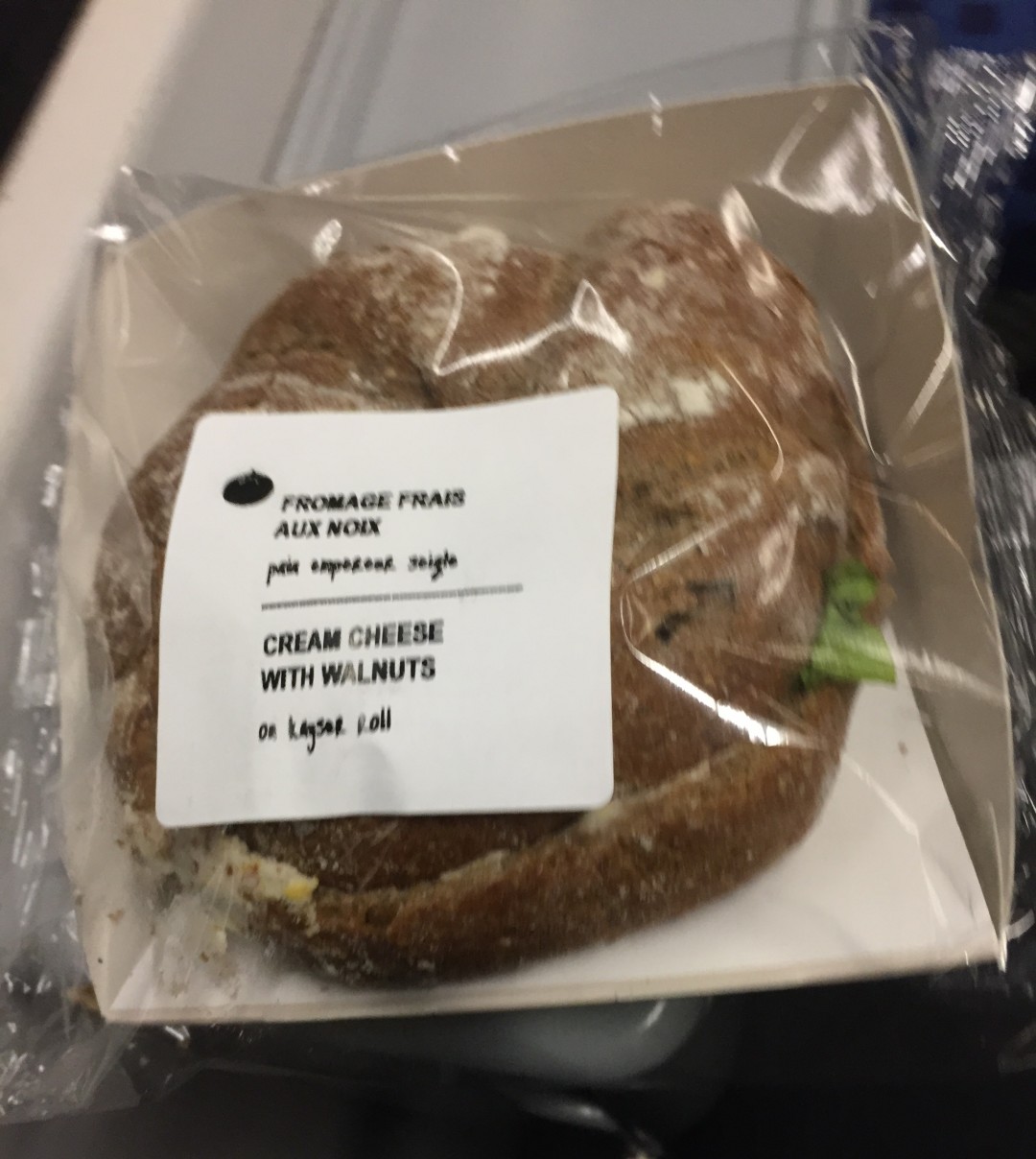

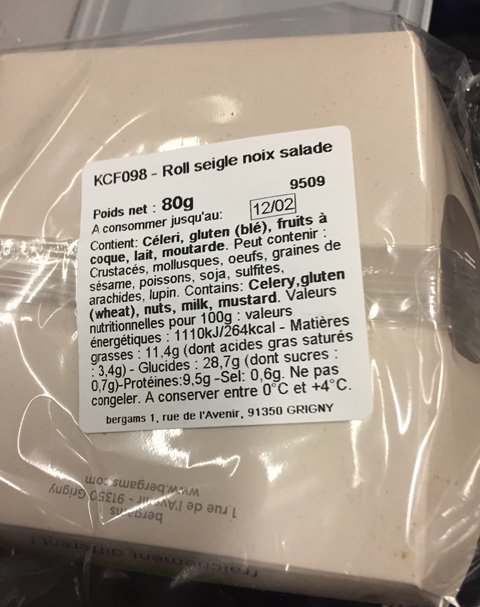

New York City, 10 Columbus Circle: this is the location of one of the 430* branches of Whole Foods Market, an organic supermarket chain for which, according to the Handelsblatt trade journal, Amazon forked out around USD 13.7bn in June 2017. The concept is aimed at eco-conscious residents in big cities, and scores points for a quite unbelievably opulent assortment of organic foods at equally opulent prices, typical for New York.

Although at first glance Dublin is not really noted for the diversity of its baked products, an immense number of creative concepts are currently scoring points in the Irish capital. With its small pastry shops, bakeries and cafés, Dublin is in no sense trailing behind the trendy metropolises. Perhaps that’s also just due to movers and shakers like the two sisters Regina and Yvonne Fallon from the “Queen of Tarts” pastry shop, who returned to Ireland after learning their craft in New York in the nineteen-nineties.

An article by Hans-Herbert Dörfner, an expert with the Senior Experts Service (SES), a Foundation of German Industry for International Cooperation, Bonn

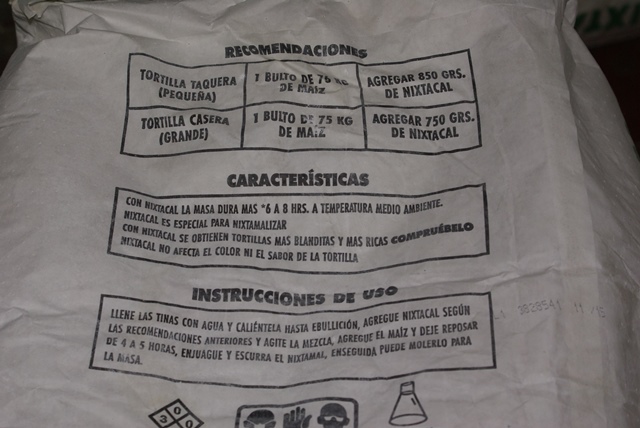

The Senior Experts Service sends out experts all over the world to communicate knowledge gained from their specialist area to the population in the destination countries. But what happens when, in the country in which he is deployed, an expert comes into contact with interesting products which, although they do not overlap with his area of expertise, do reveal deficiencies in his knowledge about the manufacture and composition of these specialties? That happened to me in Bolivia. The specialty offered in Cochabamba restaurants is called Salteña.

This baked item, which to a German observer looks externally simple, has some special features that will now be followed up. To ensure the necessary competent answers to my technical questions, I enrolled for a basic course given by a specialist.

The signboard was very promising. I thought the course instructor’s name, Anita Lehmann, sounded German. The lady did indeed have German ancestors who had emigrated to Bolivia after World War II. The German language had been lost over the course of generations, and the course took place in Spanish for the benefit of the participants, the great majority of whom were South American.

The baked product is filled, e.g. with carne (minced meat) or pollo (chicken fillet). When all the preparations were complete, the fillings were prepared in a pan with onions.

Bolivian cuisine does not economize on herbs and spices. When we Central Europeans find that eating this food takes our breath away, a Bolivian would then consider the dish to have just the right amount of seasonings.

The fillings are fried in pans, and in the final phase cooked vegetables (e.g. peas, leeks, South American potatoes etc. etc.) are added and the hot mix is deglazed with water and gelatin. In this respect the gelatin has a special function, which will be dealt with in more detail later.

The mix is then poured into molds and stored in a refrigerator.

The dough preparation also has some peculiarities: the ingredients are wheat flour, eggs, salt, melted fat, yeast, water and a vegetable food coloring to give the dough an appetizing yellow color. The question as to whether European food inspectors might suspect this to be customer deception will not be examined any further at this point.

“Learning by doing” was the order of the day, and for some of the participants it was their first experience of dough.

The dough preparation with wheat flour, eggs, salt, melted fat, yeast, water and a food coloring © Dörfner

The portioned dough pieces are prepared with a rolling pin, and the filling is introduced. Let us remember that the filling contains gelatin as binder. The mix has solidified in the refrigerator, and thus there are no problems when measuring it out. The filled dough is now shaped into a pasty, closed and sealed. However, what looks easy and simple requires special skill.

The edge of the pastry case is folded over itself again to ensure that the filling, which liquefies again during baking, does not leak out. And this is what a perfectly formed closure of a Bolivian Salteña looks like.

The pasty cases are put onto baking trays and baked at a temperature of 210°C for 25 minutes. Marginal note: Cochabamba – which is where the baking course took place – is at an altitude of 2,800 meters (ca. 9,200 ft.). The baking temperature and baking time must be adjusted to local conditions if necessary.

After being baked, the deliciously tasty Salteñas were a success and were swiftly consumed by the course participants.

Much of the evening course with Anita Lehmann seemed strange to me. The preparation of the specialty, and the teamwork with the Cochabambinos (which is how the residents of Cochabambas refer to themselves), gave me a lot of pleasure and allowed me some insights into the South American lifestyle.

Bread crates, or rather transport crates for baked products, are much in demand. So much in demand (as stolen goods) that industry experts estimate the so-called “shrinkage” at around 3% per year. This box went off course into an especially beautiful and particularly remote region. Where was it found? In the ranger’s cabin of the “Jellyfish Lake” in Palau. Its real owner is the GWF company (George Weston) in Australia, also known there as Tip Top Bakeries.